An account of Gustav Adolph Midelfart’s life

Summary of Impressions

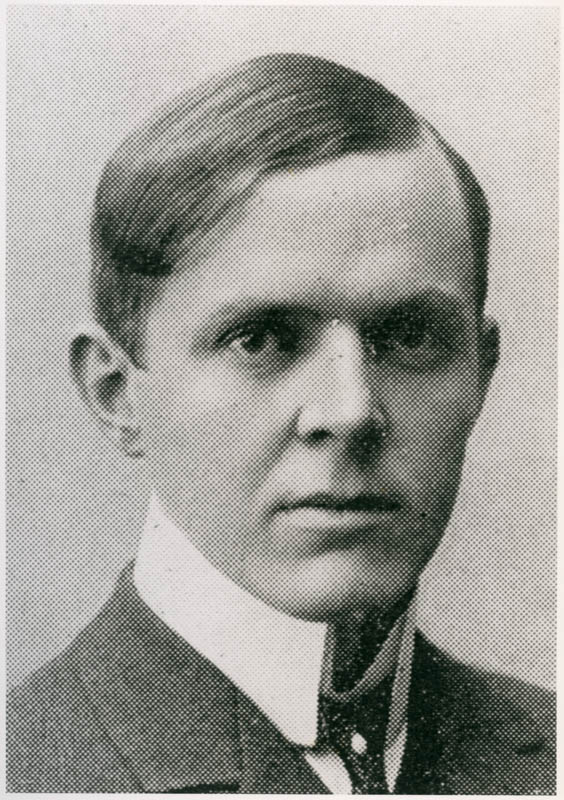

GUSTAV ADOLF MIDELFART

(1872-1924)

(Based mostly on letters written between 1897 and 1925 by Gustav and about him by his siblings.)

by

A.K. Hellum

(a great nephew of Gustav)

Written January 29, 1992.

Updated July 1, 1999.

Modified December 2007-February 2008

INTRODUCTION

What is said in this summary is based almost exclusively on quotes from old letters both from Gustav and from several of his family dating from the period 1897 to 1925. The letters written by Gustav to his brother Christian in the USA, and to his oldest sister Anna in Christiania, figure prominently. But they make up a small part compared to the voluminous letters Anna wrote to various members of the family in which she talks about Gustav and his exploits. Anna says in one letter from 1897 that she feels responsible for the Midelfart family because their mother, Nicoline Margrethe (née Solberg) died at Kobbervik on August 15 in 1888, when Anna was not yet 26 years old and Gustav, the youngest, had not yet reached 16. And when their father, Peter Albert Midelfart, died on September 16, 1896, she became the oldest in the family. However, Peter Albert seems to have exerted little influence over the children judging by the scanty mention in the letters. It has been said many times that Christian, as a boy, went to live at Kobbervik in Drammen because he could not get along with his father in Christiania. He even finished high school in Drammen with his cousin and friends there. Kobbervik was the childhood home of his mother, Nicoline. It is a mystery why the mother’s name is not referred to in any of these letters numbering over 200, except for one comment on her pious and kind nature made by Anna’s younger sister Ingeborg Stang Lund. In fact, the father’s name does not crop up in one single letter that I translated.

It is my understanding from most of the letters written about Gustav that everyone thought that he had to be protected from himself. Family members seemed to think that he had poor judgement in most things and that he lacked self-discipline and was too impressionable to function without his family’s constant guidance even well after he left law school in Christiania in 1896. But maybe more significantly, the family kept on lending or giving him money to bail him out of many difficulties at least until he reached his mid-forties. This was well after he had left Norway permanently. The dependency, which this created, was verbalized by Gustav in many of his letters and he felt diminished by all his debts and broken promises to repay. What is not found in this large collection of letters is the reason why he developed into such a dependent person. But maybe it can be deduced from what was not said.

EARLY YEARS

Gustav was the youngest of the five siblings of Nicoline and Peter Albert Midelfart who reached adulthood. Anna was born in 1862, Wilhelmine (Mina) in 1864, Christian in 1865, Ingeborg in 1870 and Gustav in 1873. (October 12). He was therefore nearly three years younger than his closest sibling Ingeborg. The first three children were born over a mere three-year period and probably felt very close to each other as a result. And Gustav was less than 16 when his mother died. It became clear from Anna’s letters to her brother Christian, that she saw her position as being tesponsible for holding the family together and in line and for protecting the family name and reputation. For example, in 1897 she expressed her anger at Christian for not writing more often and more in detail about his own life in Wisconsin. She demanded more news to which Christian retorted by sending her a registered letter only five written lines long and to which he expressed his frustration (anger?) very forcefully. But Gustav never got out from under her gaze until he left Norway in 1908 and Europe in 1913 bound for Southern Rhodesia via Capetown. He was then 40 years old. Up until that time Anna wielded strong influence over his actions and she was quick to judge them critically. It might well be that she wielded strong control because Gustav was so young when their mother died. It had become a habit. Christian was already in medical school in 1888, the year Anna bore her first child in marriage to Dr, Med. Axel Holst. Anna and Axel had married already in 1883. But the tone of many letters suggests that because Gustav was the youngest, he was considered in need of guidance from all four siblings. He clearly felt this dependence witnessed by his repeated pleading for financial help.

GUSTAV’S LAW PRACTICE

There is a rumour that Gustav started law studies in Christiania at the University but that he never finished them. This is not true. He graduated in 1896 from Fredericia University in Christiania. His student picture appeared in the Student Union annual report for 1896. This is the latest available picture of him that I know of. The picture was taken when he was 28 years old. In other words, the annual report was printed about seven years after his graduation. We know the date of the photograph because Gustav received the report from one of his sisters and he commented that the picture dated from 1901. This letter suggested that Gustav had trouble getting good cases to handle but that he, legally speaking, was in a position of authority to handle them.

He probably left Christiania in 1896 as a clerk in Kongsberg under the direction of judge Heffelmehl, who apparently was a friend or acquaintance of the Midelfart family. At first, he seemed contented but then he got progressively more and more bored. He ended up spending much of his time copying documents by hand for the judge and he lamented that the practice was very small in any case. Kongsberg was not a good place for parties and entertainment either, and Gustav liked a better social life than what this little town could offer. Kongsberg did offer him easy access to hunting in fall times and skiing in winter both of which he enjoyed very much. After just one year there, by December 1897, he wrote to his brother Christian that he was looking for a legal job in Christiania. By July 1898 he had a substitution job in a law firm of Mr. Schiander while Mr. Schiander’s assistant was away on travels for a year. By this time business for lawyers in Christiania was booming because the business sector was experiencing a down time with bankruptcies and business closures and land speculation was causing many people to worry about the future. It was then Gustav’s intention to travel in Europe after this year to study French and English.

In early 1899 Anna lent Gustav 3,050 crowns of Christian’s money in Christiania so that he could play the stock market or to speculate on land prices and sales in Christiania. There is a note from Anna to suggest that he paid back only 500 crowns of this loan. Anna wrote Christian, after having lent Gustav the money, saying she hoped her brother didn’t mind. She justified her action by saying that Christian would get his money back with regular bank interest “at any time” and Gustav would have some money to speculate with at a cost lower than he could get at the bank. She confessed that she and Axel did not have access to money of their own to lend him for such speculation.

The correspondence from Anna to Christian in 1900 bears no mention of Gustav but he was abroad for much of this year. There was mention of him having been in both Paris and London, and he stayed for several months in London towards the end of 1900. It was here that he went to the Hotel Continental, apparently a house of ill repute, where he made the acquaintance of Ida Olsen, a prostitute. He fell head over heels in love with her. He married her probably in December 1900 in London and did not tell his family about it until after the fact. Then he wrote Anna saying as much as: I have married, and I know you will not approve, so I will not come to see you and any criticism of Ida will be taken for criticism of me.

From January 1901 on he lived in Christiania with Ida. Her real name was Ida Rosenvind Sørensen. The name Olsen was probably from the wheelwright she married once in Copenhagen before the turn of the century. Rosenvind Sørensen was her father’s name but he had disowned his mother and her. Ida’s mother had apparently been a maid in a hotel where Mr. Rosenvind Sørensen had made her pregnant and then she was fired from her job.

Gustav tried to make a go of it in law in Christiania, but he had to beg and borrow money from many sources to stay alive. He apparently had trouble collecting money for services rendered. Ida wanted a good lifestyle with attendances at theatre, eating out and drinking champagne from time to time, and Gustav struggled the best he knew how to satisfy this appetite. He was a willing partner to this lifestyle.

By 1904 he sold some worthless (?) shares to a family relative and at another time he sold other worthless shares to someone else also in the family. People were very kind to him. But Ida was often in London during the time between 1901 and 1905. Her business there was not mentioned, but it is tempting to speculate that she had returned to her “old” trade. Anna lamented her returns to Christiania.

But by 1905 he had convinced many in the family to buy a law practice for him in Stockmarkness on the small island of Hadelsøya at 68º North in Lofoten for 5,000 crowns. He was to share this with lawyer Rynning and get to handle larger cases through this other lawyer’s credentials and contacts. Gustav left Christiania and neglected to pay for his groceries bought at Syvertsen’s amounting to over 637 crowns. But the family had its doubts about the success of the venture in Stockmarkness and Anna wrote that she had no illusions about success. Christian was contacted by the Syvertsen store and asked if he could help in the matter of settling the unpaid grocery account. Ida decided she did not want to go to Stockmarkness at all and remained in Christiania. And Anna makes this comment in one letter that there was a fire at Ida’s shortly after Gustav left. Anna thought: How advantageous. Apparently, Ida made something of the event claiming insurance money.

But the event of Ida Olsen cannot be left out here. Ida was apparently an illegitimate child of a wealthy man called Rosenvind Sørensen and a hotel maid. The father disowned the child, and she apparently became a hawker on the streets of Copenhagen just like her mother who was fired from the hotel when she became pregnant. Ida married a wheelwright, by the name Olsen, and later lived with a wine merchant and then a gardener. She was a registered prostitute in Copenhagen in 1897 and had several run-ins with the police over petty thefts. As a prostitute she had the reputation of “being the most intriguing woman around the house.” Quite a reputation. She was admitted to hospital in 1897 for gonorrhea but did not have syphilis at that time.

Ida evidently set up a business with her gardener friend to sell the flowers on the streets of Copenhagen from the garden of the gardener’s employer. When they were found out the unlucky gardener got three years of hard labour while Ida went scot free because it was not possible to prove that she knew that she had sold stolen goods.

After this she left Copenhagen with what Anna calls her “Alphons”, whoever that was, and plied her trade from Hotel Continental in London where Gustav met her.

The Midelfart family did everything it dared to do, short of sending Gustav over the edge mentally, to break up the marriage. They tried to say it was illegal by digging up dirt in Copenhagen through Andreas Pedersen, a close friend or relative of the family. They found out that Ida had not divorced Olsen when she married Gustav, so they tried to have his marriage annulled. They tried to break the spell she had over him by interrupting their lived together. For example, Anna went to Gustav and Ida’s hotel room unannounced, one time, to get him out of bed to come to a meeting which the family had arranged, and which he had agreed to attend but avoided by sleeping-in. They even refused to send him his inheritance to Copenhagen in 1901 saying that he would have to sue them for it to force him back to Norway.

By 1905 he had moved out of Kristiania to Stockmarkness and by 1908 he was in London and by 1913 he left Europe alone for Africa.

OTHER ACTIVITIES

There is no record to show who paid Gustav’s unpaid grocery bill at Syvertsen’s and by December 1907 Anna had to send Gustav 3,050 crowns to help him out in Stockmarkness and there was also some mention of another time when she had to pay one of his bills. But by April 1908 he seems to have given up on the law because he was in London. He was said to have taken many of his belongings to London and sold everything in Norway.

By November 1909 Gustav was in Copenhagen again trying to cash a check for 25 pounds sterling and he had told Andreas Pedersen there that he was working as a correspondent for the New York Herald out of Paris. By 1909 he was again living with Ida in Copenhagen where she was sporting fancy attire and jewels enough to be mentioned in Dagbladet in Kristiania. She had apparently inherited a good sum of money and jewels from her father after his death. Gustav wrote bragging letters at this time to his Solberg relatives in Norway and Anna explained this to Christian in letters to him. But Gustav apparently had not contacted his closest family at all. He was quoted as saying to Andreas Pedersen in Copenhagen that “if his family could get along without him, he could certainly get along without his family.”

By May 1913 things had turned so sour for Gustav that he boarded a lumber ship bound for South Africa. He said he had good introductions in Rhodesia, probably Southern Rhodesia because he spoke of the wonderful climate. His friend Arthur Mathiesen had got him free passage, first class. From this time on Ida does not figure in his life, judging by the letters now available. There is one exception to this. A note was made in one letter from Gustav dated May 10, 1922, in which he says that Ida had written him a long letter but that he had to confess that he has been “completely cured” of what he called “my former wife”. In fact, he befriended a French lady called Louise Garrabos in the Belgian Congo sometime between 1913, the year he arrived in Africa, and 1923. He was then in Brussels and had his will rewritten. In it he excluded Ida and included Louisa. There is no mention of a legal divorce from Ida.

But good luck did not follow Gustav to Africa. He arrived in Rhodesia in the fall of 1913 via Capetown at the end of a two-year drought. There was no work to be had anywhere then. He wrote home for fifty pounds sterling from his family so that he could take a course for six months in how to become a chauffeur, but even though the family sent at least part of the money he did not stay this term. It is worth mentioning that Anna wrote to Christian in Wisconsin to make sure that Gustav had not also asked him for fifty pounds and at the same time asked if Christian would join the family in Norway in sending fifty pounds from the whole family, in several installments.

In January of 1914 he is again asking for money, this time for sixteen pounds sterling by which time he had been unemployed for 4½ months in Bulawayo and had to pawn most of what he owned. He admitted to being depressed by the whole business of staying alive, but otherwise his letters were consistently upbeat and optimistic. He said that he had been retained by Union Miniére in the Belgian Congo in the Haute Katanga province. He had worked for the Busanga Mine before. Now he was apparently going to work for the Kambare Mine at 5,200 feet in altitude. He was happy about being able to escape the heat and the terrible insects of the lowlands. He blamed his 4½ month unemployment time on the war. He says his wage fell from 225 dollars a month at the Busanga Mine to 120 dollars at the Kambare Mine. But he also says that of the 2,100 francs that he got (from family or from the pawned items is not known) he used 1,800 (or 360 dollars) to stay alive while unemployed.

But the Kambare Mine job did not materialize, apparently because of the war, he said. By October 1914 he was working near Elizabethville on the railroad in up to 125ºF (51.7ºC) heat every day. He tells of 95 of the 100 men who made up the work party he was on getting malaria and being very ill and dying all around him. He was lucky to stay uninfected, probably because Anna was sending him quinine. He also described the death and desolation brought about by the tsetse fly killing not only humans but also pigs and other wild game. He tells of finding corpses of humans who were the last to die and could not be buried. Village after village stood empty of life. It must have been an eerie experience putting in a railroad in such country.

In December 1914 he thanked Christian for the fifteen pounds sterling sent him through South Africa and Capetown. He had been working for Pusey and Payne before writing but he had damaged his hand in an industrial accident using a heavy tool of some kind and could not do heavy labour and lost his job. He was again in Bulawayo by this time and had got into contact with one Colonel Colenbrander about managing hunting parties, safaris, for two Austrians. He was hoping for more such work later.

Already by February 1915 he was writing to Fredrik Stang Lund asking about work in Norway. But his letters were ambivalent for in April he wrote his sister Ingeborg (Fredrik’s wife) that he was happy staying in Africa and by July he said he had a three-year contract with Union Miniére again in the Belgian Congo. By September he was reported to be in London, England.

Gustav did not come to Norway in 1915 but stayed in London the whole time. He was destitute and Fredrik Holst, Anna’s oldest son, who was working in London, went to him and gave him first ten pounds sterling and then 1,000 crowns as an advance on his inheritance from his aunt Elise who had just died in Drammen. He used this money to buy clothes for the tropics and to see a dentist, among other things. Fredrik saw him often during October of that year and this brought Gustav a little closer to the family. This pleased Anna very much.

When in London Gustav had experienced a zeppelin bombing attack that could have cost him his life. A bomb fell 100-200 meters from where he was, and he said he nearly lost his hearing from the blast. It is interesting to note that the letter he wrote to Anna in Norway and from London about this event was cut to ribbons by the sensor but the similar letter he wrote to Mina from Spain got through unscathed. He left London on November 6, 1915, for Africa again with a contract to work for the Forminiére diamond firm, a consortium of Belgian businessmen and the financier Guggenheim from the USA. He was to travel to the Kasai diamond fields in the south of the Belgian Congo and live at about 700 meters above sea level where they had ample water, milk, and vegetables and where they were apparently free of the dreaded mosquito.

By the first half of 1916 he was writing home steadily to his sisters. In December 1916 he was in Tshikapoo (also called Tshikapa) running a chicken farm on the Kasai River. He tells Anna that he has people from 12 tribes working for him (he calls them races) and he says he does not share Anna’s difficulty in telling one Negro from another. He also spoke Kiswahili by this time and was struggling to learn one of the local dialects also. But he found the grammar very difficult. He also apparently spoke fluent German, French and English by this time, apart from Norwegian.

By early November 1916 he was at Tshikapa working for Societé Internationale Forestière et Minière du Congo developing and running a farm that was started to supply the large labour force needed in the diamond fields in the Kasai with food. He said that up to 3,000 labourers worked in his immediate vicinity and that, with their families, they numbered around 5,000 people.

In this letter he tells Anna of his work, that the place is rainy in November but that most of the rains come at 5 p.m. and at night but that the native people suffer from bronchitis if they are asked to work in the rain. He says the weather in the mornings can be misty and cool, just like a fall day in Norway and that he has had bad trouble raising chickens because of red ants killing them or the humidity getting to them. His plans to break 200-300 hectares of land had been put into practice as soon as he had got there four weeks earlier and that four hectares had been broken already and planted to corn. He planned to increase the three teams of four oxen to five teams when he could obtain more plows. He complained about the poor American administration but that there was ample money to pay for things that had to be done.

By late 1916 he says his first crop of corn was 14 days away from harvest, in mid-January, and he had found a way of getting the heavy logs out of the steep river ravines using 20 oxen and a steel cable. He tells of his garden with nearly ripe tomatoes and celery roots from Norway and about the fruit tree seeds he asked for at the nearby Luluabourg Mission. He worried about food supplies having been ordered too late from Europe to prevent starvation and he complained again about poor American administration in Tshikapa.

By February 1917 he had planted the following shrubs and trees in his planned fruit orchard:

200 lemon, orange and mandarin trees

500 grapefruit trees

50 mango trees

100 papaya plants

100 banana palms

100 plantains

and some maraconjas, grenadilles, Brazil nuts and cocoa palms as well as “Coen de Boeuf” and advocate pears.

And he had broken and planted 60 hectares of land to crops. His chickens had all died due to red ants and possibly also high humidity and he worried that he would lose his oxen due to overworking and maybe also because they might be taken from him and used for other purposes.

This farm needed sheds for 300 cattle and 150 sheep and goats. He had 100 natives working for him. He was well into this work by April 1917 and Anna became impressed that her youngest ne’er do well brother was so practically inclined. He admitted to having saved enough money by this time to start to pay off some of his debts, but he says he is afraid of doing so because he has nothing for his older age when he would leave Africa. By 1917 he was 44 years old. In response to this Anna wrote Christian with a question. Would he want to join the others in Norway in setting up an annuity for Gustav in the range of 2,000-5,000 crowns? She also tells of her son Fredrik sending Gustav quinine pills from London because she is worried constantly about his ability to stay healthy “down there”.

By April 1917 he is growing celery and beans from seeds sent him by Anna. And he is thankful for this variation in his diet.

On the first of February 1918 he wrote that he was still working for the Societé Internationale Forestiére et Minière du Congo from the Kasai Diamond Fields, Tsikapoo, Kasai. He is talking of coming to the end of his contract in April there and that he is going hunting either near Katanga or near Lac Leopold II, and he says he has permission to shoot “even an elephant”. He tells of sitting typing that letter in total darkness because the sun had just gone down. His ability to type without looking at the keyboard stood him in good stead, a skill he probably developed during his first years in Africa when he would do anything to stay alive. He told Anna in March 1917 that he was going to the Cape Colony for a rest and to be in a healthier climate.

At this point Anna says that: “He always writes satisfied letters, but he doesn’t ask and doesn’t expect much from life anyway”. That might be true in her terms, maybe, but it was not true at all for him for he mostly expressed optimism about what he was doing. She also says repeatedly that the climate of Norway would not suit him anymore and that he “does not want to stay here even if he came for a visit.” Does all this say that he was not wanted back in Norway by his family, regardless of what he might think to write? It certainly might seem that way because when my mother Anna Louise Midelfart (Hellum) was in Oslo in 1923 she walked down Carl Johan with Anna. At one point she said to mother: “Look up in the window on the second floor of the building across the street. There is a man standing in that window. That is your Uncle Gustav. This is the closest you will ever get to him.”

1st June 1919 his address was c/o Forminiére, Tshikapa via Luebo, Belgian Congo. This was a Belgian company under American management using Guggenheim money, at least in part. And he had spent nearly half a year in the Cape Colony because of a terrible flu epidemic for which the Belgian Congo had closed its borders. He had gone down to take a vacation and got caught there. He could not get back to work. During this time, he helped bury people in Capetown, including a Swedish sailing captain. He said 400 died daily there in a population of 80,000.

Gustav kept writing to his sisters in Norway through 1919 to 1920, but very little of this correspondence was available to me for translation. The reason for this hiatus in the mails is not known. He again talked of a trip home during this time. But his trip did not materialize until 1923 when he had informed people that he was coming home home on April 1. But Gustav stayed in Europe for only a few weeks because he was already on his way down to Capetown again on May 4 from Southampton, England. During this time, he visited England, Belgium and Norway. That much is known. His ship docked in England, he had his will rewritten in Brussels and he was seen by family members in Oslo. Anna and Axel Holst went to Brussels to see him when he was there. Their son Fredrik also came from London to be with him while his parents were there. Gustav stayed only two days in England before boarding his ship for Capetown again. Anna says in a letter dated July 1, 1923, that: “It sounds as if it was hard for him to say goodbye to us all this time.” But family attitudes towards Gustav had not ameliorated, even by 1923, for Anna would otherwise not have talked to my mother about Gustav the way she did. Mina said in a letter from around 1923 that she felt badly treating him and Ida so coldly in Christiania while they were there, but she said her feelings of solidarity to the rest of the family prevented her from being friendlier to them.

Gustav returned to Africa in May 1923 to handle a large cattle drive. He said he was to drive 2,000 head of cattle 1,000 kilometers through partly uncharted territory from Rhodesia to Tshikapa in the Belgian Congo. He was hoping to reach Tshikapa by Christmas 1923. The drive would take over half a year from start to finish and for this he was to get 650 pounds sterling plus expenses. His last known address was c/o Forminière, Kanda-Kanda Kabinda, Congo Belge via Capetown. Anna said that the cattle drive had not started by July 1923. He had apparently convinced his employer to buy inexpensive cattle in Rhodesia and walk them to the Congo where they were very expensive.

What actually happened on this cattle drive is described by a man called Chaloux in 1926 in a book he wrote called Un An au Congo Belge (pp.298-300) and by one Marthe Coosemans who wrote a summary of Gustav’s activities in the Congo in 1955. He apparently left Tshikapa on April 28, 1923, for Katanga in charge of buying cattle in Rhodesia and getting these to Haut-Katanga where the Forminière had established a huge cattle-breeding station. He traveled with five other Europeans on this drive, with Belgian Veterinary Varlier, Mr. A. Smith, a South African resident from Elizabethville who was a promoter of the cattle breeding project on the Bianos Plateau and who provided meat for the butchers in the capital of Katanga, and Mr. Smith’s three sons.

The cattle that were bought came from the Kafue region in Rhodesia on a tributary of the Zambesi River of Northwest Rhodesia (Zambia). The drive consisted of 1,883 cows, 333 calves, 50 bulls and 100 steers. In total this was 2,366 head of cattle. The cattle were first taken by train to Bianos Plateau 160 km south of Bukama and after a rest the drive started on August 3rd, 1923. The drive took five months. It was escorted by 200 blacks but only 50 of these (Rhodesians) really understood cattle. They crossed the vast plateau and descended towards the Lualaba River. They forded this river, and all went well. The cattle were calm, there were no stampedes even though lions surrounded the drive and stealthily followed it day after day.

The drive moved by day and the cattle foraged as they went whenever food was available. One of Gustav’s jobs was to scout out the route to make sure that the cattle find food and water. Sometimes he had to split up the herd because the food was too sparse and sometimes he had to walk the cattle without finding food for them during traveling. Sometimes the natives of the region they traveled through had burned the grass so that there was nothing for the cattle to eat. Corals had to be built every night for the cattle so he sometimes planned travel so those different groups of cattle could use the same corrals night after night. There were in all fourteen tributaries that they had to cross between the Lualaba and the Lubilash rivers.

Gustav left ahead on foot accompanied by black helpers. He checked out the best routes and then sent runners with directions to the rear. The drive was divided into three echelons, and these moved according to the lay of the land. Because the food was always a problem during this dry season, the cattle echelons had to be divided into regiment, battalions and smaller companies to be able to forage as needed. Twice a day the animals were counted. The blacks didn’t know how to count that high, apparently, but they got to know the animals well enough that they could account for the ones they were looking after. They would come to announce, for example, that the black bull with only one eye missing or that the cow with tufts of white hair behind the left ear was missing. A search would be mounted, and the animal again found.

The drive traveled at the average speed of the slowest unit. On average the drive covered 12 km and on slow days they might cover only three kilometers and on the fastest day they covered 32 km. Sometimes the drive proceeded at night when food was scarce to be able to cross the area as fast as possible.

But by and large the cattle camped during the nights. The boys would arrive, built the kraals in several hours and make them hold 200 animals per kraal.

There were births en route. This slowed the drive down and young calves were put on carts or were carried on the backs of the blacks to minimize this slow-down. The calves were allowed to trot along as soon as they were old enough to do so. But calves did become separated from their mothers. When this happened, the search went on and on until calves were reunited with their mothers.

The boys who stood watch by each kraal would light huge bonfires to keep the lions away. Acetylene lamps were also used to keep the wild animals away. The lions would roar, the boys would stoke the fires, and in this way the drive lost only one animal to lions and only one cow drowned in a river because it was a poor swimmer.

This makes up the accounts written down by Chaloux and Coosemans.

On the 23rd of September 1924 Axel Holst wrote a hasty letter to his son Fredrik in London in the hope of intercepting Christian who was leaving for America via Southampton. Axel had just received a letter from Gustav’s employer in Belgium that Gustav had been killed on a hunt, on or about July 20, 1924. Gustav had apparently shot and wounded an elephant that then charged him, picked him up and threw him on the ground and before his native helpers could come to his rescue the elephant had trampled him into the ground. He had completed the long cattle drive by Christmas 1923 and probably was on a hunting expedition when he was killed. In fact, he was leading a hunting expedition when he was killed.

Gustav’s sister Ingeborg had visited with him while he was in London in 1923 and they had gone shopping together, and Fredrik had bought a present for him contributed by his sublings before he left for Africa again. This last time of meeting seems to have been a loving and caring time and Fredrik wrote with great feeling about his uncle in a letter that he sent together with his father’s letter to Christian who had already left for America. Five paragraphs from this letter bear repeating in full:

“My childhood memories of Uncle Gustav are associated with Kobbervik where he and Uncle Carl S. smoked cigarettes in the library and for me this represented Alpha and Omega wisdom. A fool they said to me, can ask more questions than 10 wise men can answer.

Uncle Gustav and I often shared a bedroom together, the one that you entered first when climbing the library steps. He then used to have some lively quotes from Samson who had the mouth of a donkey, and the Philistines were afraid of it etc. Once he gave me Nøstvedt’s history, and like him, it was of good humour, a spark in the eye. Destiny would have it that he was here in London during 1915 when mother sent me his address. I went over to visit with him, and I did many things for him, as many as I could manage. He was here and made good friends with the ladies, ate dinner, drank claret and smoked (with us). He did not look well that time.

Last year we were all together in Bruxelles and he visited with me here, then he was leaving. I have him, after discussion with mother, a good suitcase with a cover from his siblings. He looked well then and I thought to myself that I surely should see him again.

Mother’s death touched him deeply and he wrote a letter to me that showed this. I wrote back to him and said that as long as the flag was flying from my masthead here, he would be welcome in my house. You know it wasn’t so easy just to go home. You knew his answer when you were there. That was his last letter.

I think that we can be in agreement, that Uncle Gustav has had a wonderful death when he died on the hunt. Hunting permeated his letters like a red thread. It was, I think this can be said of the, from that time when his life was good to him and his. It was also his hope for the future. He talked about coming home some time to sell tusks and hides, you know. He hoped to save enough money and come back to Europe to live – with his own people. But maybe it is written in the stars somewhere that this plan should not be realized in a way that would have pleased him. Maybe therefore he was torn away from us.”

But in late 1924 Ingeborg Stang Lund received a nice letter from Gustav’s former boss in Forminière telling her about Gustav’s death based on the final police report. Gustav had gone hunting with two natives, one Dala Padimba who had hunted with him before, on July 9. They had immediately found an elephant that Gustav fired at but the two bullets only wounded the animal which screamed in pain and charged Gustav who reloaded. But his third shot also failed to stop the raging animal. It picked him up and threw him onto the ground, uprooted many trees and piled them on top of him. The two natives ran for help from “the white man’s friends”.

Gustav was transported from Kasamba, in the Loamin territory of Mutombo-Mukulu, where he was killed, to Kongolo where the “l’Administrateur Territoriale” lived, one Mr. E Pepin. Here he was wrapped in a sheet and two blankets and burned. Mr. Pepin had a stone inscribed with his name and date of death and “a cross and large stone were placed around so that the place could be easy to recognize.” Apparently, Gustav had sprained his right hand in a bicycle accident five days before and had then hurt his foot and right eye when he had fallen into an antelope trap two meters deep on July 7, just two days before he was killed. From this it does not seem that he was in any good shape for hunting elephants. The natives mourned his death terribly.

On January 8, 1925, Ingeborg wrote to her brother Christian saying that one of the directors of Forminière told the Norwegian contact in the Congo, Mr. Fredriksen, that the company had never had such an honest man in their service and that Gustav was irreplaceable for them. This seems a very fitting turn of events for a man burdened with his guilt about his past in Norway. And Ingeborg agonized over receiving anything from Gustav’s estate saying she had given him so little in his life. The pain still moved the heart.

While Gustav was in Belgium, he prepared another will in which he spelled out how the money he left behind was to be divided. He had grand hopes for what he could leave behind. He died too soon for this to happen. He left money for Louise Garrebos, for the children of his three sisters and for deserving civil servants in Norway, but what he left behind was too modest for what he wanted to do for others. He had saved 80,000 Belgian francs and 360 pounds sterling, a princely sum for him after all his struggles. But it was not much for being divided among so many people as he had intended.

After his death, when the new will was read, Axel wrote to Christian that he would try to have the will changed so that very needy members of the family, who had not been mentioned by Gustav, could get some share of his legacy. Axel mentioned especially Fredrik Stang Lund Jr’s widow. Even after his death Gustav’s wished could not be taken seriously.

Jon Bergsland in Oslo told me in April 1999 that he had seen a tusk from the elephant that killed Gustav. It was labeled as such. It was on display in the Golden Gate Museum where he visited in 1947 in San Francisco, California. It therefore seems tempting to speculate that the hunting party was American that Gustav led in July 1924 when he was killed. I wrote to the Guggenheim family about this but never had any reply. It is a fine epitaph for Gustav. He broke the family mold. He struggled most of his life to gain respect and a position he could feel good about. He managed this finally, but his death snuffed out his opportunity to benefit much from it. This summary is incomplete without a picture of this epitaph and maybe someday it might be included here, if I ever could get to Zaire. I wrote to the Museum in San Francisco and asked them about this tusk, but they had no record of this event at all.

But Gustav added mystique to the respectable Midelfart family, and of a kind very different from the importance of Hans Christian Ulrik Midelfart who sat at Eidsvold in 1814 or Hans Christian Ulrik Midelfart in Wisconsin. When mother told me that her aunt Anna said she would never meet him in person even though he was in Oslo in 1923, this story burnd itself upon my mind. I was too young to take note, however, but I had a teacher in high school in Larvik, probably around 1948, whose name was Rynning. He came up to me wanting to speak about Gustav for he was related to the lawyer Rynning with whom Gustav had practiced in Stockmarkness so many years ago. I did not respond for I did not understand until much later, and I was too young anyway to be truly interested in genealogy. I was still a dreamer about Gustav. Maybe I still am that dreamer.

All this writing about Gustav would have been impossible had it not been for my grandparents never throwing away letters when storing them in their attic in 343 Gilbert Avenue in Eau Claire, for Margaret (Maggie) gathering them up and saving them after her mother’s death in 1951, for her sisters who found the suitcase containing these letters under Maggie’s bed and saving them after Maggie moved to an assisted care facility, for the chance I had in 1992 to become aware of them, when my aunt Elise asked if I would translate a letter from Gustav, and were given them to translate for family. History sometimes hangs on a very thin thread indeed. And I missed two opportunities to know more about Gustav yet when I heard of the tusk and spoke to my teacher so long ago. To share this writing with others has been pure joy and a true labour of love.

A.K. Hellum

Summary of Gustav Adolf Midelfart’s life by Marthe Coosemans

March 8, 1955.

(A.R.S.O.M. Bibliotec Coloniale Belge Bxl 1958, Volume V.)

Agricultural engineer and Doctor of Laws (Oslo, 12, 10, 1893- Kasamba, Loamin, territory of Mutombo-Mukulu 9. 7, 1924) Son of Peter-Albert and Madeleine Solberg.

Studying in the Faculty of law of the Royal Fredericia University of Christiania, he obtained his doctoral diploma with distinction. He wanted, however, to study agriculture and subsequently obtained a diploma of Agricultural Engineering.

Equipped with many excellent references, he presented himself at the Mining Association of Haut-Katanga which hired him in 1914 as an administrator. After the 1914-18 war he began work with the Forminière (Union of Forestry and Mining in the Congo). On April 28, 1923, he left for Katanga, in charge of buying cattle in Rhodesia and getting these animals to Haut-Katanga where the Forminière had installed a huge cattle breeding area. Joined by another European, the Belgian Veterinarian Carlier, Midelfart set out with a certain Mr. Smith, a South African resident from Elizabethville, who was a promoter of the cattle breeding project on the Bianos Plateau and who provided meat for the butchers in the capital of Katanga.

Midelfart and his two companions traveled to Northwest Rhodesia where they bought 1883 cows, 333 calves and 50 bulls for the Forminière. This was in the region of the Kafue, a tributary of the Zambesi. The animals were transported by rail to the Bianos Plateau, 160 km south of Bukama.

On the 3rd of August, after a short rest, the caravan set out, with Midelfart at the head, Smith and his 3 sons and Carlier and 200 blacks guarding the animals.

They crossed the plateau and descended towards Lualaba, fording the river and making at least 10km a day. Having crossed wooded savannah, burnt and dried plains, with stops to construct kraals, the group arrived with very little damage or loss of animals. One cow was taken by a lion and a steer died on route.

Midelfart had been able to carry out this mission surmounting great difficulties when on the 9th of July 1924, during a hunting expedition, he was killed by an elephant.

There was never any mention in letters that Gustav had a Doctor of Laws, that he had graduated in law with distinction nor that he had got a diploma in Agricultural Engineering. Take the above with a grain of salt!

The Odyssey of a Cattle Drive

(from Chaloux’ book of 1926 Un An au Congo Belge as translated from the French by Hilary Hellum).

The Forminière, whose diamond mines we visited a month ago, decided in the spring of 1923 to create a huge cattle breeding station.

M. Midelfart and M. Carlier (Carpentier?), the well-known veterinarian left, contacting M. Smith, a South African, a longtime resident of Elisabethville. He supplied the large center with meat and owned pastures on the Biano Plateau, a tributary of the Zambezi in Northwest Rhodesia.

The drive which we are going to tell you about consisted of 1,883 cows, 333 calves, 50 bulls and 100 steers. In total this was about 2,400 head of cattle.

The cattle were first taken by train to the Biano Plateau 160 km south of Bukama. There they rested and on the 3rd of August in 1923 the huge drive began its match. The drive took five months.

Personnel: M. Midlefart at the head, then M. Smith with his young sons, 3 herdsmen and M. Carpentier.

The undertaking is new and fraught with difficulties. Two hundred black escorted the drive, but only 50 (Rhodesians) understood the cattle. They crossed the vast Plateau and then descended towards Lualaba (Main Congo). They forded the river, and all went well. The cattle were calm, there was no stampede as happens often in Argentina or in the far West. Attracted by the livestock, lions surrounded and stealthily followed the enormous drive.

By day they moved and ate. However, there was not always the necessary food. Sometimes they crossed regions of wooded savannah or places where grass was completely non-existent because the natives had burned it. Advantages: there were no tornadoes, no torrential rains, the swamps were dry; there were few tsetse flies. As well, the level of the water was not high, with almost no current, making it easy to ford the rivers. (A map of the Congo will show 14 tributaries from the Lualaba to the Lubilash.)

M. Midelfart left ahead on foot accompanied by black helpers. He checked out the best routes and then the direction was sent back to the rear by messengers. The drive was divided into 3 echelons and these echelons moved according to the lay of the land. It happened that the grazing lands were use up and were very small. Thus, the echelons were subdivided into regiments, battalions and small companies. Twice a day, the animals were counted. The blacks didn’t know how to count so high but after several days, they knew their animals in detail. They would come to announce, for example, “We are missing the black bull which has one eye larger than the other.” Or “The cow that has tufts of white hair behind the left ear has disappeared.” We checked, found the beast and continued on.

The speed of the drive was that of the slowest unit. It was the same as an animal troop on the march. Thus, the speed was very slow: on average of 12 km a day. The minimum was three km, and the maximum was 32!

(explanation: Moving at night was necessary in order to cross a region without food, as quickly as possible.)

But night came, with necessary stops. The boys arrived to build the necessary kraals in several hours (square palisades for 200 animals). One kraal could be used for the animals that followed at a day’s interval, if the food was abundant enough in the region so that 2 units of the troop could feed along the same route

En route there were births, which slowed down the march. In order to avoid this slow-down, the young calves were put in carts or carried on the backs of the blacks. When the calves were able to take part in the large cortege they were allowed to trot along. However, life for young calves was distressing even the most attentive of the black cattlemen were not able to keep an eye on all the animals at once. At night or more often at the kraal, calves were sometimes missing. However, if the mothers were let out, they would return from the rear of the troop with their missing calves.

Around the kraals the boys who stood guard lit huge fires each night because the lions would roar. Furthermore, acetylene lamps were added to keep the wild animals at bay.

During the whole voyage, there were only two losses: one cow was eaten by a lion and one steer, a bad swimmer no doubt, was drowned.

What a wonderful lesson in perseverance, of virility and endurance was shown by these men.