Peter goes on to explain that times since the “revolutions” have been much, much harder for Christians that before. While he admitted that Mubarak stole money and placed it in Swiss banks, he said that at least there was work enough for all, and that Muslims and Christians lived in relative harmony. According to Peter, there appears to be a concerted attempt to persecute Christians here. When young Christian girls go missing, attempts to have a report written with the police are refused. Refused! His hard-earned income has been further degraded by having to buy metal bars to put on the outside of his apartment’s windows. His rent is 450LE a month (CAD$75), and there are times when he goes without work 2 weeks at a time. All this and more flooded out of him. As we approached the central ticket booth for the Valley of the Kings and Tombs on the West Bank, he looks sadly at his feet and apologizes for saying all this. Its clear he lives in fear for his life, and that of his wife and two young girls (11 and 10). I am struck dumb by his admissions and feel an overwhelming swamp of guilt for the way in which I live in Canada. “Christians live free in Canada?” he asks. Yes, I say, there are many, many Christians in Canada, and many Muslims too. He is surprised that there are Muslims in Canada, but nods in understanding when I say that there are also many Jewish people.

I see a man beside me driving our minibus; conflicted with guilt at wishing to leave Egypt as so many have done, wanting desperately to ask if we would have any pull at getting him and his family out of Egypt (although this is never brought up, it lingers as subtext to the entire conversation), and shame at not providing a better life for his family. His wife cannot work, as she appears to be required to wear a hijab (not something required in any way in their religion), and only opens the door to him on his return home. I am left wondering if their collective fearfulness is feeding on itself and expanding. But I can only take him at his word, and he is most certainly an honourable man. I admire him greatly and am at a loss as to how to help.

All of this for him, in just two short years.

Peter drops us at our main objective for the day, Medinet Habu (“meh-deen-ett hah-boo”). Like many of the sites we are visiting, I first trod here 20 years ago. I made two subsequent visits to Egypt before this one, and each time have found myself shooting photographs in much the same way I did initially. Rules at the sites change over time (I can no longer walk the walls above Habu), English signage improves (no more “No climping on the tomps”, sadly), and there are new areas revealed through excavation that were flat desert before.

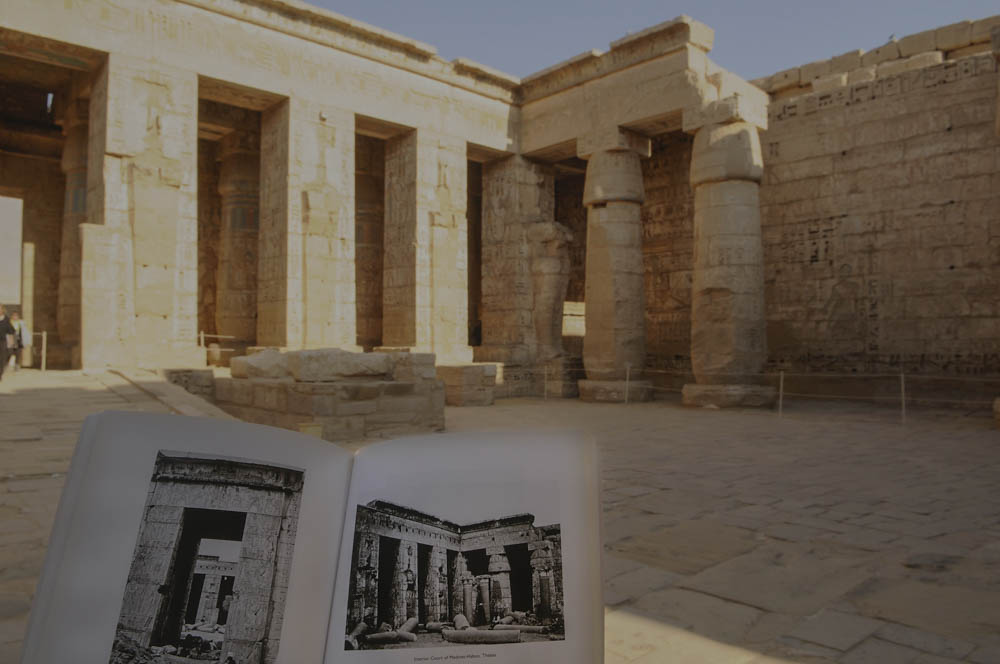

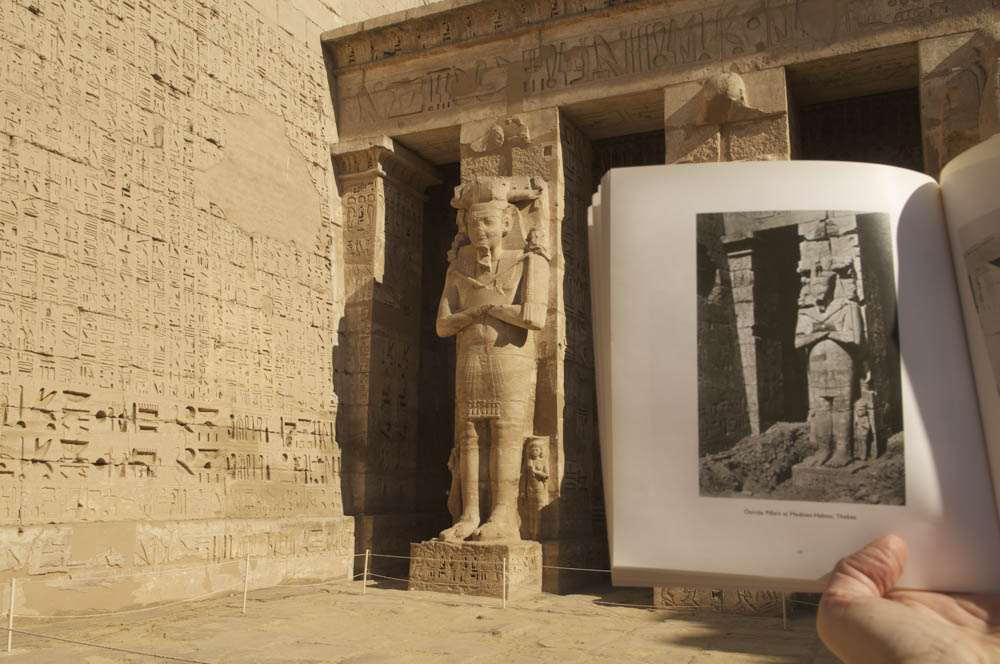

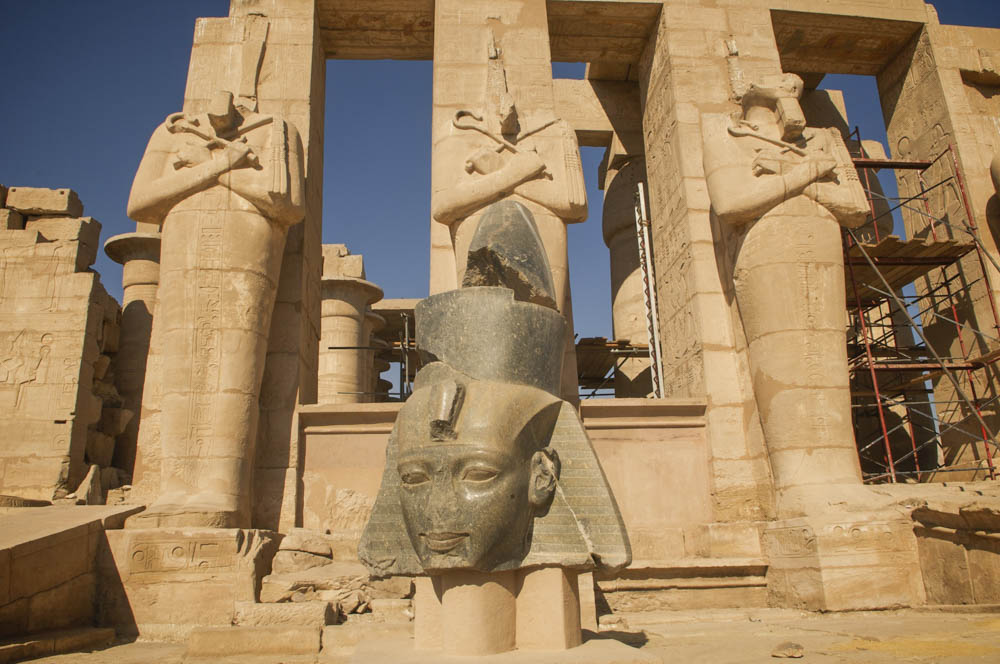

Habu has been my favourite site since the beginning. Its remarkable state of preservation, and careful restoration stand in stark contrast to the wholesale rebuilding of Deir al Bahri (Hatshepsut’s temple). Habu is quiet, under-rated, retains the most paint on columnation and ceilings of anywhere we’ve been, and has a beautiful procession theme from outer to inner pylon structure, and further to interior courtyard(s). Pylons are those massive walls at the outset of a temple, struck down the middle for main entrance. You’ll see a few of them in photos on this journal. I remember a wise instructor I had at Ryerson, a prof for art history. He showed us a series of images of the Parthenon, ending with an interior image of a small, columnated portico inside the front entrance. “Why, do you suppose, this small portico exists before the main entrance to the interior of the structure?” No one could guess. “Its to prepare you for what you are about to experience, to provide visual insight for the grandeur that lies beyond.” Of course, I thought, how perfect. And I see this at work at Medinet HAbu as well. I have posted too many images of Medinet Habu here, but indulge me if you will. I have been unwell and bedridden for most of two days since.

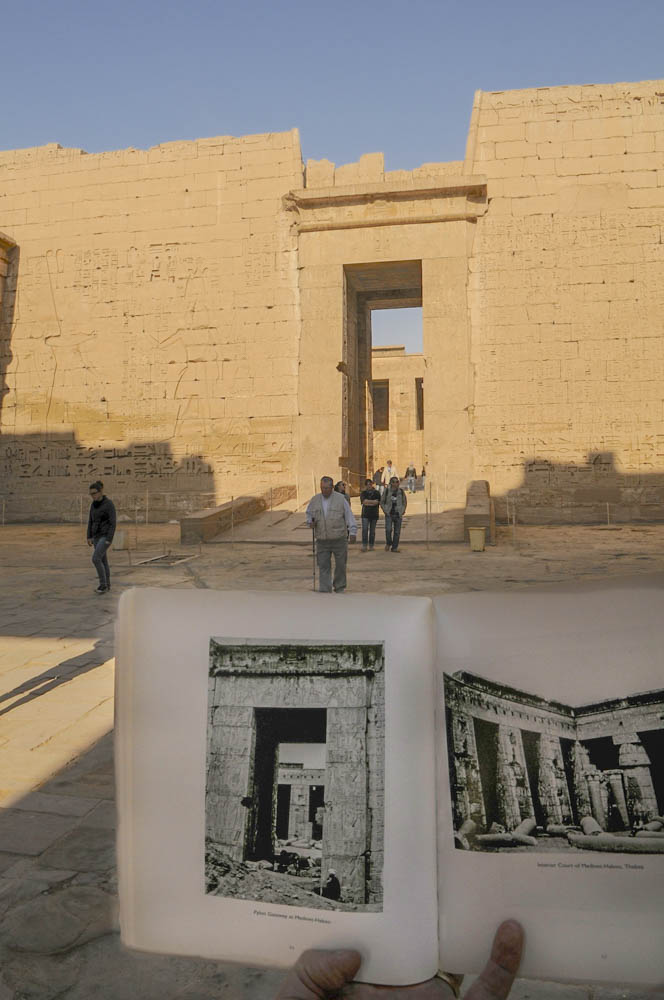

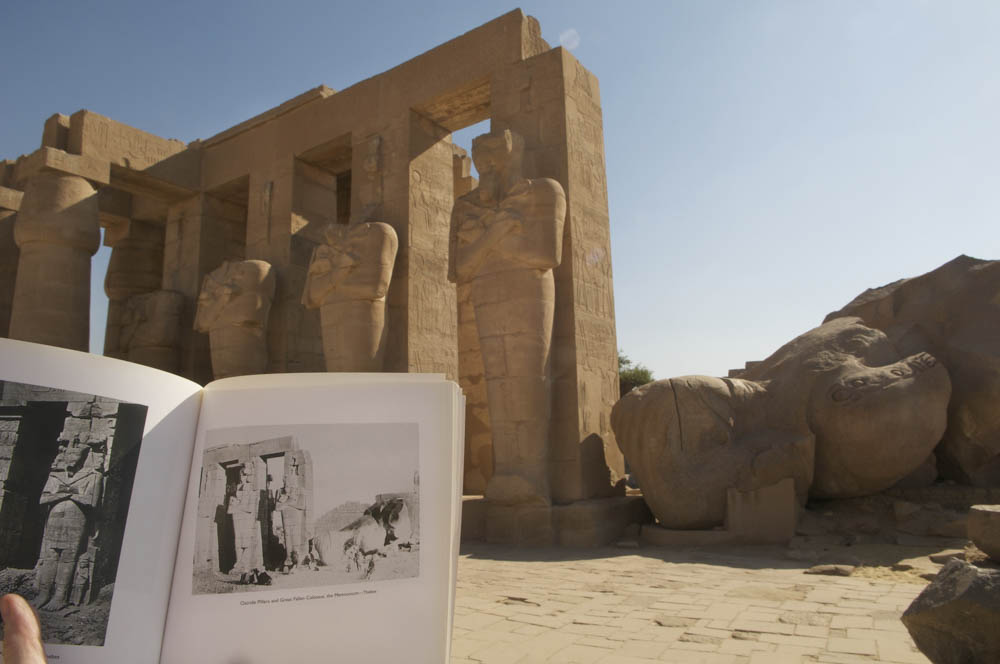

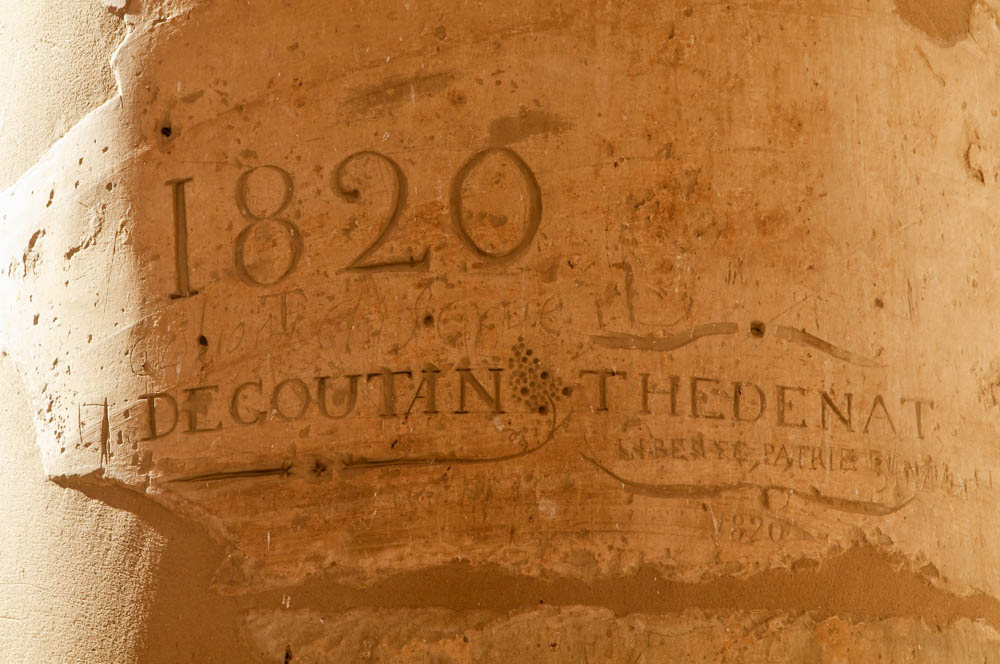

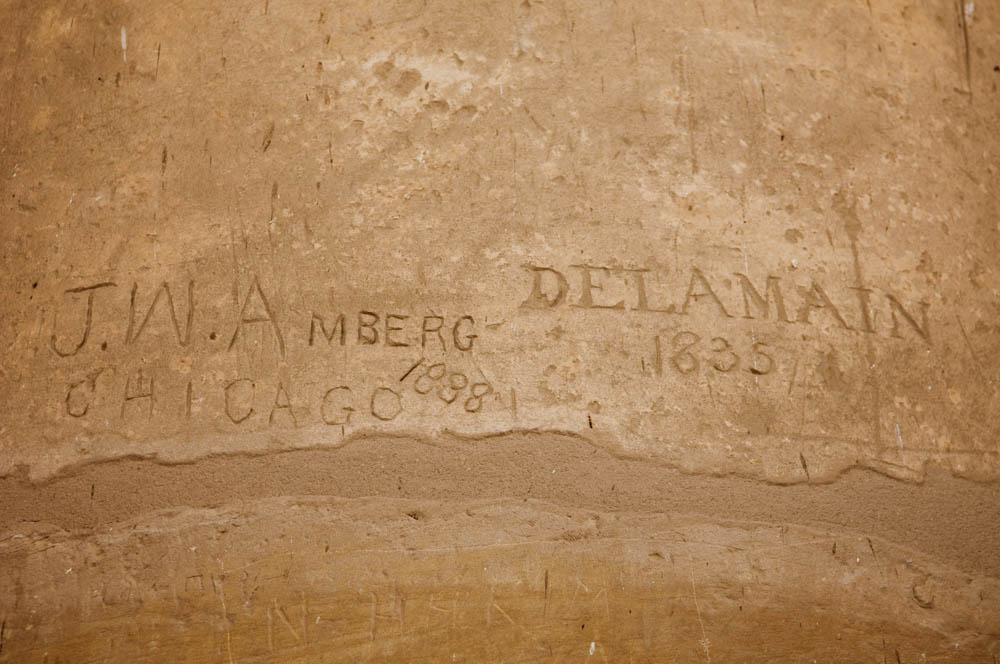

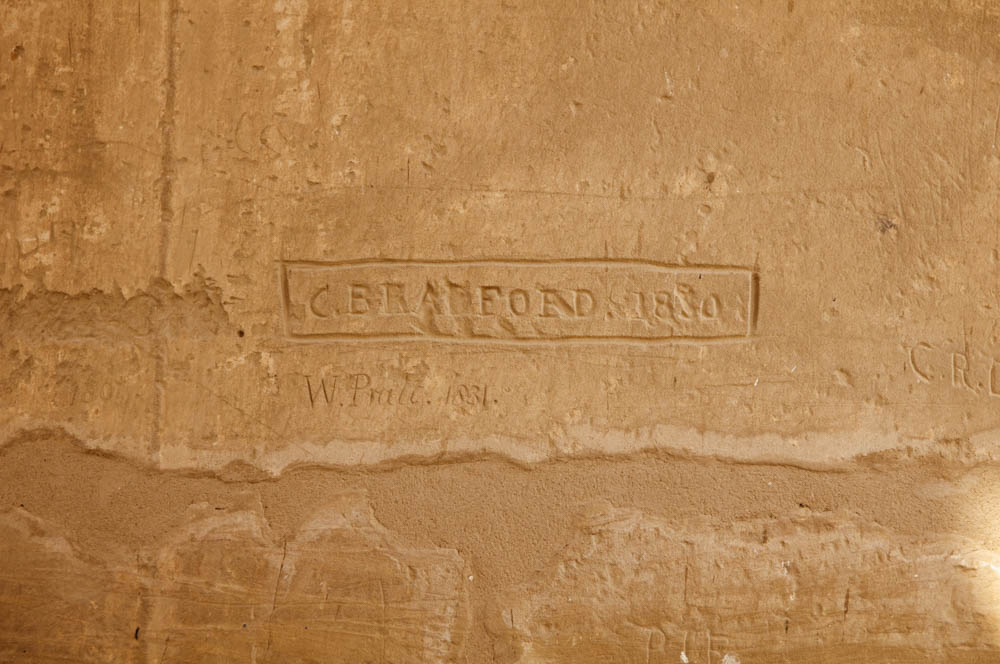

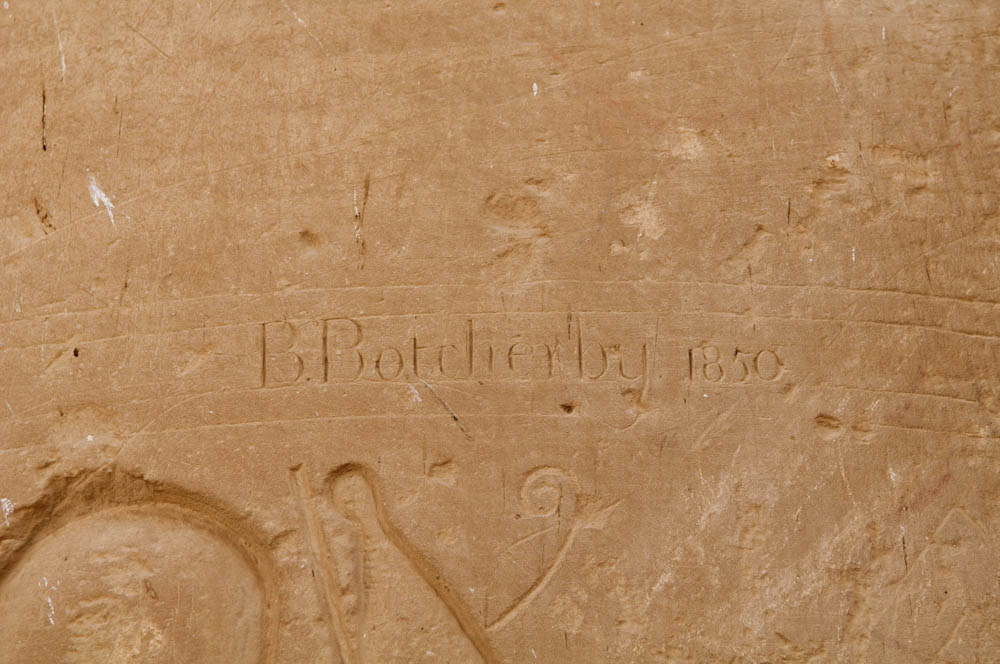

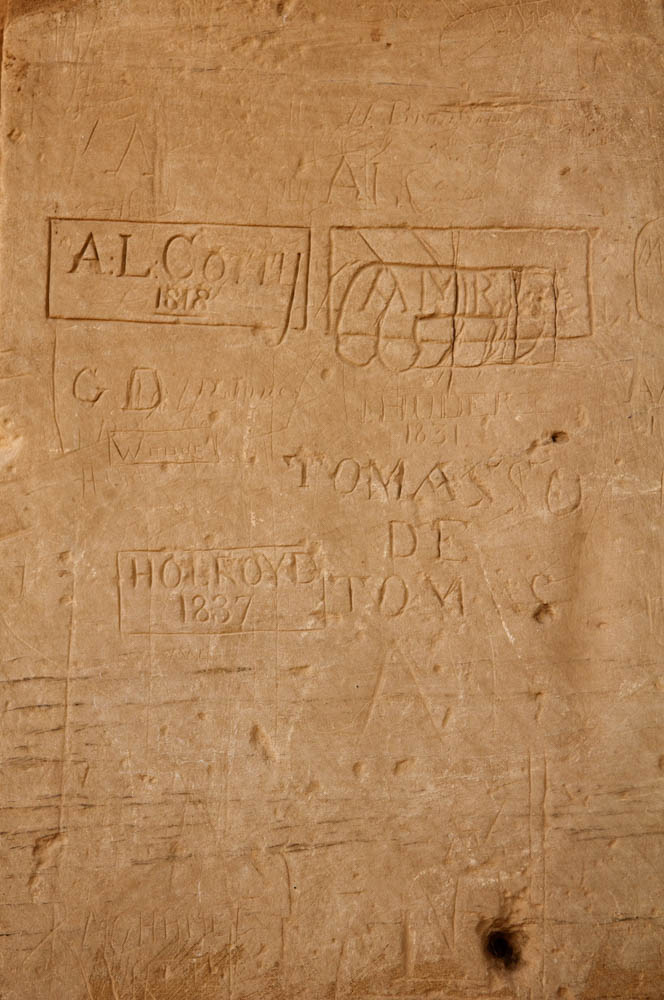

Note that in several images I am holding a photo book in the frame, followed by a standalone image of the scene as well. I am carting around a book of plates by Francis Frith, pre-eminent photographer of the levant in the 1850s. I thought it might be interesting to see his images from 150 years ago alongside ones shot today. I have also included a number of interesting images of graffiti, many pre-dating the discovery of the source of the Nile. However, Finn very rightly took me to task when she asked why it was OK to be interested in old graffiti, but to frown heavily on some we saw dating to 2008. I immediately declared my admiration for her query and said only that I did not have an answer. She suggested that in 150 from now, the 2008 grafitti might be just as interesting as that we saw from 1818.

We also visited the Ramasseum temple after Medinet Habu and there are some photos from there as well.

Hi Tim,

It is easy to understand your continued fascination with Habu simply by looking at your photos here. And kudos to Finn, for catching you out. Made me grin. Smart girl.

The story of your driver reminds me I must pick up Kamal’s book, Intolerable. My innate interest in Middle Eastern culture, esp. its architecture and art, is always tempered by the ongoing conflicts that bring hardship and worse to so many.

I do hope you’re feeling better. I’ll be thinking of you, en famille, as we head into the New Year and wishing you all well.

It’s been such a treat to follow your Egyptian adventure from Paris on. Looking forward to more.

Cheers,

Henri